Who should go first in a negotiation when it comes to offering a price, solution, and agreement to key terms?

Do you ask for a budget and then craft what you do from there?

Or do you, once you know what the needs and major parameters might be, suggest a solution and a price before talking about budget?

It’s a common question, one that continues to baffle many sellers. They fear that if they go first, they will leave money on the table, or risk going too high and having the buyer say, “That’s nowhere near what we were thinking,” or anything in between.

The research available up until now has suggested it’s in your advantage to take the lead and go first. It’s been somewhat commonly cited, for those who know the academic research on negotiation, that 85% of negotiated outcomes align with the person who goes first.1

But that was based on a classroom study by college professors. Is it true? Is it applicable for business sellers who usually have more complex negotiations?

Absolutely!

I share more in this video (and below) about who should make the first offer in a negotiation.

The RAIN Group Center for Sales Research recently completed a study of 713 business-to-business sellers and buyers (both business buyers and procurement) to see what top-performing sellers in sales negotiations do differently than the rest.

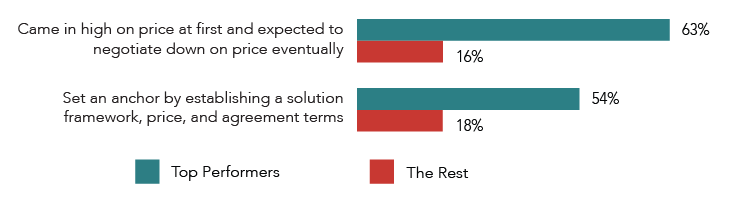

Of the 14 negotiation tactics by sellers we studied, here are two of the top three most effective.

Effectiveness of Negotiation Tactics Used by Sellers

By % Very Effective

We also studied the most effective tactics buyers say they use with sellers.

We also studied the most effective tactics buyers say they use with sellers.

Of the 16 tactics buyers use with sellers, the 4th most effective for buyers was “Sharing a low budget up front to set the stage for bargaining to start at a low price.”

Effectiveness of Negotiation Tactics Used by Buyers

By % Very Effective/Effective

Whoever makes the first offer, whether seller or buyer, is usually more effective in the negotiation.

The power of first offers is strong thanks to the science of the anchor effect.

Anchoring is an irrational part of human decision making—what’s called a cognitive bias. (For other cognitive biases that impact negotiations, such as loss aversion and the sunk cost fallacy, check out The #1 Way to Decrease Anxiety and Gain Leverage in Sales Negotiations.) When making a decision, people strongly favor the first piece of information they receive. They orient their subsequent evaluations around this information and it anchors how far their final decision can go.

Anchoring is one of the 16 negotiation tactics buyers use as identified in this infographic.

To demonstrate the completely arbitrary nature of anchors, behavioral economist, Dan Ariely, asked people to write down the last two digits of their social security number.2 Then, he asked them to consider whether they would pay this amount for items—wine, chocolate, or computer equipment—of unknown value. Afterwards, participants bid for the items. Those with higher social security numbers submitted bids that were 60-120% higher than those with lower numbers. The digits from their social security numbers had become anchors.

First offers act as anchors in your negotiations. The other party will fixate on them. Even if concessions move the final solution, price, or terms away from the first offer, the final result will likely still be closer to your ideal than if the buyer had made the first offer.

What Happens When the Other Side Goes First?

If the buyer ends up going first, don’t ignore it. Their number gives you critical information about where they're coming from. However, share your offer quickly and think about how you can unhook their anchor. You might say:

"Thanks for sharing that. I’ve also prepared a set of terms that works for us and right now there are some marked differences. Let me share them with you. Then let’s discuss."

The Power of Anchoring

Even seasoned experts can’t escape the effects of anchoring. Back in the 1980s, researchers from the University of Arizona asked real estate agents (experts) and students (amateurs) to tour a Tucson property and estimate its value.3 The participants were given packets with information including recent real estate sales for the city and immediate neighborhood, characteristics of other properties in the neighborhood, and the standard listing sheet for the property.

On average, the real estate agents had been selling real estate for 7 years. Only 15% of the students had ever been involved in a real estate transaction at any point of their lives.

Everyone received the same information, except for one key piece: the current list price of the property being evaluated. The participants randomly received one of four different list prices: a high price (12% higher than the actual list price of $74,900), a moderately high price (4% higher), a moderately low price (4% lower), and a low price (12% below).

Before running their experiment, the researchers had been warned by local real estate agents that anyone with experience would quickly notice that the "extreme" prices were obviously inappropriate.

Not only did the fake listings not raise any red flags, they influenced the appraisals of all the participants—amateur and expert alike. The experts were slightly less affected than the amateurs, but the same trend held true: people with low anchors kept their estimates low, people with high anchors kept them high.

When asked, the real estate agents denied using the list price in making their appraisals. They pointed to features of the property that justified their estimates. But the data begged to differ—the anchor price had significantly influenced their decision. The real difference between the amateurs and the experts? The students acknowledged they had used the price in the information packet when making their estimate.

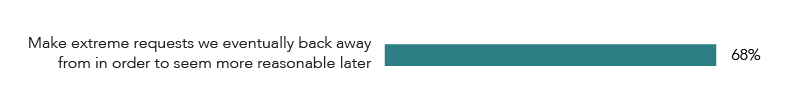

According to our research, this is a very effective tactic buyers use with sellers. In fact, 68%(!) of buyers who use the tactic “Making extreme requests we eventually back away from in order to seem more reasonable later” say it is very effective, or effective.

Effectiveness of Negotiation Tactics Used by Buyers

By % Very Effective/Effective

When to Ask for Budget

You shouldn’t always go first. There are situations where you might ask for a budget before making an offer. Here are a few of those situations:

- When you know they buy similar products/services and you're trying to displace a competitor. You can say something like: “What do you typically spend?”

- When talking to your champion. You can say something like: “What’s actually going to work here in your opinion? What’s the investment tolerance? What are the competitors offering?”

- When they say, “That’s not in the budget.” You can say something like: “Okay. What’s the budget?”

- When you know they use internal teams to do something you could do for them. For example, they have 10 staff people working on X, costing $Y, and you could do it for $Z with many value-adds.

From social security numbers to real estate values to our breakthrough research on sales negotiation, anchoring isn’t rational at all and it affects even experts in their fields.

So, if you’re wondering who should make the first offer in a sales negotiation, you should. Whoever makes the first offer tends to obtain the better outcome.

1 Adam Galinsky and Thomas Mussweiler, "First offers as anchors: The role of perspective-taking and negotiator focus," Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 81 (2001): 657-669, https://psycnet.apa.org/record/2001-18605-008.

2 Dan Ariely, George Loewenstein, and Drazen Prelec, “Coherent Arbitrariness: Stable Demand Curves Without Stable Preferences," The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 118, no. 1 (February, 2003): 73–106, https://doi.org/10.1162/00335530360535153.

3 Gregory Northcraft and Margaret Neale, "Experts, Amateurs, and Real Estate: An Anchoring-and-Adjustment Perspective on Property Pricing Decisions," Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, 39 (1987): 84-97.